Turning Audit Logging into a Shared Library in a Fintech Microservices System

Audit logging is one of those things that sounds simple until you actually have to do it properly.

In a fintech system especially a multi-tenant one audit logs aren’t optional. You need to know:

- who did what

- from which service

- on which tenant

- and at what time

At first glance, it feels like something every service should just handle on its own.

That assumption is what got me thinking deeper.

Why I didn’t want audit logic inside every service

The obvious solution would have been:

- add audit logging logic to each microservice

- push logs to a database

- move on

But that approach breaks down quickly.

Each service would:

- implement audit logic slightly differently

- evolve its schema independently

- log different levels of detail

- become harder to reason about over time

Worse, compliance questions would turn into:

“It depends on which service handled that request.”

That wasn’t acceptable.

So instead of solving audit logging per service, I treated it as a platform concern.

The decision: audit logging as a shared library

Rather than building a central audit service that every microservice had to call synchronously, I built a shared audit library.

The idea was simple:

- every service imports the same library

- audit behaviour is consistent everywhere

- services declare what to audit, not how

From the consuming service’s point of view, it’s just:

- add a dependency

- annotate the method

- configure a message broker

No duplicated logic. No drift.

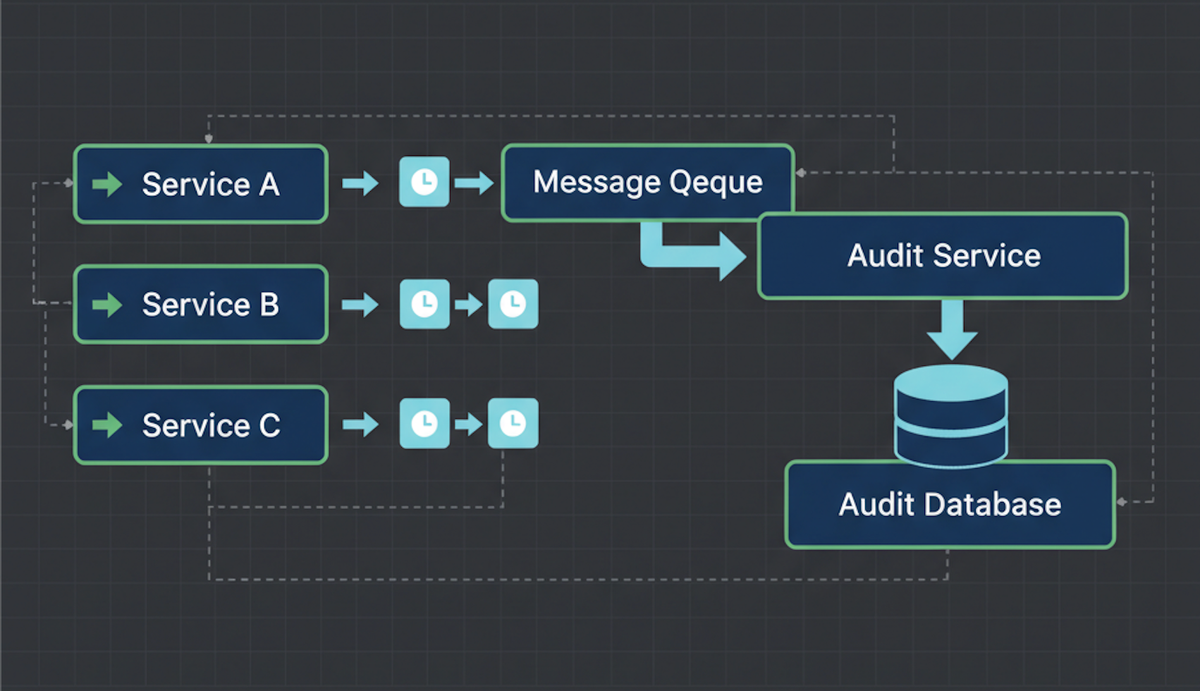

High-level architecture

At a high level, the system looks like this:

- Microservices

- use the shared audit library

- emit audit events asynchronously

- Message broker (RabbitMQ)

- decouples audit logging from business flow

- Audit service

- consumes audit events

- persists them to MongoDB

- exposes filtering by service, operation, user, tenant

The important part:

Business logic never waits for audit logging to succeed.

Audit failures shouldn’t block onboarding, or updates unless explicitly configured to do so.

How auditing is injected without touching business logic

The key technical decision here was using Spring AOP.

The audit library exposes a custom @Audit annotation, and internally uses an @Around advice to intercept annotated methods at runtime.

This is important.

By intercepting at the method boundary — not at the HTTP layer — auditing works consistently for:

- controllers

- service methods

- internal calls

- async flows

Using ProceedingJoinPoint allows the audit layer to:

- capture method arguments before execution (request context)

- proceed with the actual business logic

- capture the return value or exception (response context)

All of this happens without polluting domain logic.

The consuming service doesn’t need to know how auditing works only that it exists.

What it looks like for a consuming service

From a consuming service’s perspective, integration with the audit library is intentionally minimal.

There’s no SDK to learn, no client to manage, and no audit specific business logic scattered around the codebase.

Adding the dependency

The service simply imports the audit library like any other internal dependency:

<dependency>

<groupId>com.bestcompany.worldauditlib</groupId>

<artifactId>bestcompany-audit-library</artifactId>

<version>0.3.0</version>

</dependency>

Once this is on the classpath, the auditing infrastructure becomes available automatically through Spring.

Required configuration

At minimum, the consuming service only needs to declare:

- its service name (used for attribution)

- a RabbitMQ connection string

spring.application.name=payment-service

spring.rabbitmq.addresses=amqp://user:password@rabbitmq-host:5672

That’s it.

Annotating what actually matters

Auditing is opt-in and explicit. A service only audits what it chooses to audit.

Here’s a simple example:

@Audit(

activity = "User Login",

isMetaDataRequired = true,

failOnError = false

)

public AuthResponse login(LoginRequest request) {

return authenticationService.authenticate(request);

}

A few things are happening here:

activitydefines what is being recordedisMetaDataRequiredcontrols whether user and tenant context is attachedfailOnErrordetermines how tightly this operation is coupled to audit reliability

This makes auditing a design decision, not a side effect.

When audit failure should not block the request

Most endpoints fall into this category.

Read operations, non critical mutations, or user facing actions should continue to work even if the audit pipeline is temporarily unavailable.

That’s why failOnError = false exists.

If RabbitMQ is down:

- the business logic still executes

- the request still succeeds

- audit failure is logged internally

This prevents operational issues in the audit pipeline from cascading into user facing outages.

When audit failure must block the request

Some operations are different.

For example:

- payments

- balance changes

- irreversible state transitions

For these, audit guarantees matter more than availability.

Here’s what that looks like:

@Audit(

activity = "Respond to Chargeback",

isMetaDataRequired = true,

failOnError = true

)

public ChargebackResponse respondToChargeback(ChargebackDecisionRequest request) {

return chargebackService.processDecision(request);

}

Chargeback handling is a high risk financial operation.

Failing fast on audit errors prevents irreversible state changes without an audit record.

Why failOnError exists

The failOnError flag was added after a real incident.

We had a period where RabbitMQ was unavailable, and because auditing was synchronous at the interception point, every audited endpoint started failing including ones that shouldn’t have.

That forced a clear distinction:

- Which operations require audit guarantees?

- Which ones should remain available even if audit logging fails?

Instead of baking in a global rule, the decision was pushed down to the method level, where the context actually exists.

This keeps the system flexible without sacrificing correctness.

Why we record both request and response (intentionally)

One thing worth calling out explicitly is how auditing is handled across the lifecycle of a method call.

We publish audit data twice per operation:

- once before execution

- once after execution

This is intentional but it does not mean we create two unrelated audit records.

Under the hood, a single process identifier is generated at interception time and reused throughout the method’s lifecycle. The same audit object is enriched as execution progresses.

In practical terms:

- the pre-execution publish captures intent and input

- the post-execution publish updates the same audit context with the outcome

This ensures that:

- failed operations still leave a trace

- partial executions can be investigated

- intent and outcome are correlated using the same process identifier

Rather than creating duplicate records, this approach produces a single logical audit trail that evolves over time.

There is some additional messaging overhead but in systems where traceability matters, the ability to reconstruct what was attempted is more important than optimizing away a second publish.

This was a deliberate tradeoff.

Improvements I’d make before open sourcing it

1. RabbitMQ connection handling

The initial version uses the raw RabbitMQ client.

That works, but it comes with tradeoffs:

- manual connection management

- fragile channel reuse

- limited resilience

For a public library, this should move to Spring AMQP, which gives:

- connection pooling

- better error handling

- cleaner abstractions

This is the first thing I would change.

2. Decoupling from RabbitMQ entirely

Right now, the library assumes RabbitMQ. That’s fine internally, but not ideal for public adoption.

A better design would introduce a small abstraction something like an AuditPublisher interface with pluggable implementations:

- RabbitMQ

- Kafka

- SQS

- even maybe HTTP

The audit library shouldn’t care how events are transported only that they are.

3. Event schema versioning

Audit logs live long.

Without schema versioning:

- older consumers break

- historical data becomes harder to reason about

A simple version field in the audit payload would go a long way.

4. Servlet vs Reactive

This implementation targets Servlet based Spring boot applications running on:

- Tomcat

- Jetty

- Undertow

The audit library relies on:

- Spring AOP method interception

HttpServletRequestfor request-level context- thread-local security and request propagation

Because of these, the current implementation does not work with:

- Spring WebFlux

- Netty based reactive servers

- Reactor driven execution models

Reactive applications handle request lifecycles and context propagation differently.

A future iteration of this library will separate audit lifecycle capture from transport concerns, with dedicated implementations for servlet-based and reactive applications.

Using Spring Boot’s conditional auto-configuration, the appropriate audit module can be selected automatically at runtime without requiring consuming services to change how they use the @Audit annotation.

Final thoughts

This started as a task to “add audit logging”.

It ended up becoming:

- a shared library

- a platform decision

- and a lesson in treating cross cutting concerns seriously

Audit logging isn’t glamorous.

But when it’s done right, everything else becomes easier:

- compliance

- debugging

- trust

I plan to rebuild and open source this properly with the improvements above and any one I discover while documenting the journey.